Strategic Planning Overview

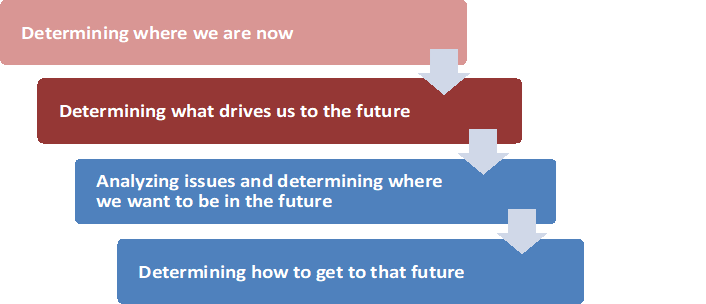

A strategic plan is a framework for describing the organization’s key processes, people, and technologies at a specific time in the future (typically 3–5 years) and how the organization can reach that future, given its current processes, people, and technologies. To ensure that the plan serves its purpose, the institution — as embodied in its strategic planning team — must fully understand its current state, as well as the factors that will impact and drive it into the desired future state. Figure 1 shows the major components of the strategic planning process.

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there,” paraphrases the Cheshire Cat from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. And if you don’t know where you are now, you won’t be able to find the right road to where you want to go.

So, the first step in any strategic planning process is to determine where you are now, or the current state. Once you know that, you can begin to look at factors that are driving you to the future and begin discussing how those drivers will (or should) impact the institution.

For example:

- Will changes in teaching pedagogy (such as the flipped classroom) significantly affect the IT support infrastructure for faculty and students?

- Will new research areas such as genomics or cosmology require research computing capability beyond what the university currently possesses?

- Will the move to cloud-based computing change the basis for IT budgeting across university departments?

- Will changes in the federal funding picture alter the focus of funding sources and thereby impact IT strategy?

Issues and drivers such as these will impact an institution’s IT strategic plan. And they all require data if they are to be discussed in detail sufficient to produce that plan.

Collecting and Developing Data

Strategic planning project teams consist of committee members and resource staff providing data and other materials to the committee. The strategic planning resource staff must collect a wide variety of data and make those data available to the strategic planning committee to support each component of the strategic planning process (see figure 1). Data must be collected and developed to highlight trends, raise strategic issues (including resource concerns), and distinguish the needs of different community stakeholders (such as students, faculty, administration, and alumni).

Data must provide details as well as general statistics; merely identifying a general lack of funding (a perennial resource concern!) doesn’t provide much basis for discussing the issues. Likewise, simply identifying an absence of qualified people to perform future tasks or an absence of currently acceptable technology is also too general.

With the move to cloud computing, for example, IT departments are universally concerned about the different types of skills their staff members will need in order to work in an external service-driven environment rather than a locally supplied environment. Coupling this with the specific number of personnel available and the number expected to be needed, as well as possible training approaches, allows for a richer discussion of both people and funding.

On the technology front, data must show the technologies currently available, as well as what can reasonably be expected in the future. For example, when the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was being planned, physicists designed their distributed computing environment in anticipation of computer networking capability levels of multiple gigabits per second, which no university had yet implemented. Data showing the current and expected increase in network bandwidth (and the reduction in costs) allowed physicists to work with university IT departments to ensure that LHC expectations could be met, offering an example of effective data-driven IT strategic planning.

Determining the range and scope of data that will allow institutions to develop IT strategic plans for all constituencies will itself require planning.

The Data-Driven Planning Framework

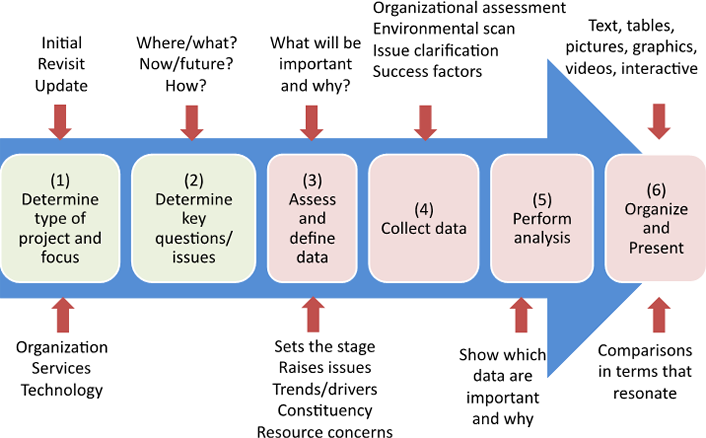

The data-driven strategic planning framework consists of two parts; the first part is a sequence of tasks to be executed during data collection and presentation (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Data-driven IT strategic planning framework

Prior to assessing which data should be collected, the strategic planning committee should

- determine the strategic planning project’s type and focus (task 1 in figure 2), and

- determine key issues and questions arising from that focus (task 2).

Strategic planning projects range from totally new activities — such as an organization’s initial strategic plan — to relatively straightforward annual or biennial updates. In between are planning projects that revisit an existing strategic plan because something significant has changed; examples include a major shift in educational policy, such as focusing on online education for remote students or a shift from in-house to cloud computing. Such projects require more than a simple update and often need significant planning and data collection. The “Data Definition” sidebar discusses how to define the data you want to collect.

Recent Comments