by nurazaliah | Mar 21, 2019 | HowTo

None is easy, but all are incredibly important.

by The Editors February 27, 2019

Carbon sequestration

Cutting greenhouse-gas emissions alone won’t be enough to prevent sharp increases in global temperatures. We’ll also need to remove vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which not only would be incredibly expensive but would present us with the thorny problem of what to do with all that CO2. A growing number of startups are exploring ways of recycling carbon dioxide into products, including synthetic fuels, polymers, carbon fiber, and concrete. That’s promising, but what we’ll really need is a cheap way to permanently store the billions of tons of carbon dioxide that we might have to pull out of the atmosphere.

Grid-scale energy storage

Renewable energy sources like wind and solar are becoming cheap and more widely deployed, but they don’t generate electricity when the sun’s not shining or wind isn’t blowing. That limits how much power these sources can supply, and how quickly we can move away from steady sources like coal and natural gas. The cost of building enough batteries to back up entire grids for the days when renewable generation flags would be astronomical. Various scientists and startups are working to develop cheaper forms of grid-scale storage that can last for longer periods, including flow batteries or tanks of molten salt. Either way, we desperately need a cheaper and more efficient way to store vast amounts of electricity.

Universal flu vaccine

Pandemic flu is rare but deadly. At least 50 million people died in the 1918 pandemic of H1N1 flu. More recently, about a million people died in the 1957-’58 and 1968 pandemics, while something like half a million died in a 2009 recurrence of H1N1. The recent death tolls are lower in part because the viruses were milder strains. We might not be so lucky next time—a particularly potent strain of the virus could replicate too quickly for any tailor-made vaccine to effectively fight it. A universal flu vaccine that protected not only against the relatively less harmful variants but also against a catastrophic once-in-a-century outbreak is a crucial public health challenge.

Dementia treatment

More than one in 10 Americans over the age of 65 has Alzheimer’s; a third of those over 85 do. As people’s life spans lengthen, the number of people living with the disease—in the US and around the world—is likely to skyrocket. Alzheimer’s remains poorly understood: conclusive diagnoses are possible only after death, and even then, doctors debate the distinction between Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. However, advances in neuroscience and genetics are beginning to shed more light. That understanding is providing clues to how it might be possible to slow or even shut down the devastating effects of the condition.

Ocean clean-up

Billions of tiny pieces of plastic—so-called “microplastics”—are now floating throughout the world’s oceans. Much of this waste comes from bags or straws that have been broken up over time. It’s poisoning birds, fish, and humans. Researchers fear that the effects on both human health and the environment will be profound, and it may take centuries to clean up the hundreds of millions of tons of plastic that have accumulated over the decades. Because the pollution is so diffuse, it’s difficult to clean up, and while there are prototype methods for tackling the massive oceanic garbage patches, there is no solution for coasts, seas, and waterways.

Energy-efficient desalination

There is about 50 times as much salt water on earth as there is fresh water. As the world’s population grows and climate change intensifies droughts, the need for fresh water is going to grow more acute. Israel has built the world’s biggest reverse-osmosis desalination facilities and now gets most of its household water from the sea, but that method is too energy intensive to be practical worldwide. New types of membranes might help; electrochemical techniques may also help to make brackish water useful for irrigation. As far as climate-change adaptation technologies go, creating drinking water from the ocean ought to be a top priority.

Safe driverless car

Autonomous vehicles have been tested for millions of miles on public roads. Pilot programs for delivery and taxi services are under way in places like the suburbs of Phoenix. But driverless cars still aren’t ready to take over roads in general. They have trouble handling chaotic traffic, and difficulty with weather conditions like snow and fog. If they can be made reliably safe, they might allow a wholesale reimagining of transportation. Traffic jams might be eliminated, and cities could be transformed as parking lots give way to new developments. Above all, self-driving cars, if widely deployed, are expected to eliminate most of the 1.25 million deaths a year caused by traffic accidents.

Embodied AI

Last fall a video of Atlas, designed by Boston Dynamics, swept the internet. It showed the robot jumping up steps like a commando. This came only two years after AlphaGo beat the world’s best Go player. Atlas can’t play Go (it is embodied, but not intelligent), and AlphaGo can’t run (it’s intelligent, in its own way, but lacks a body). So what happens if you put AlphaGo’s mind in Atlas’s body? Many researchers say true general artificial intelligence might depend on an ability to relate internal computational processes to real things in the physical world, and that an AI would acquire that ability by learning to interact with the physical world as people and animals do.

We can predict hurricanes days and sometimes weeks in advance, but earthquakes still come as a surprise. Predicting them with confidence could save millions of lives.

Earthquake prediction

Over 100,000 people died in the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami—triggered by one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded—killed nearly a quarter of a million people in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and elsewhere. We can predict hurricanes days and sometimes weeks in advance, but earthquakes still come as a surprise. Predicting earthquakes with some confidence over the medium term would allow planners to figure out durable solutions. At least giving a few hours’ warning would allow people to evacuate unsafe areas, and could save millions of lives.

Brain decoding

Our brains remain a deep mystery to neuroscientists. Everything we think and remember, and all our movements, must somehow be coded in the billions of neurons in our heads. But what is that code? There are still many unknowns and puzzles in understanding the way our brains store and communicate our thoughts. Cracking that code could lead to breakthroughs in how we treat mental disorders like schizophrenia and autism. It might allow us to improve direct interfaces that communicate directly from our brains to computers, or even to other people—a life-changing development for people who are paralyzed by injury or degenerative disease.

by nurazaliah | Mar 19, 2019 | HowTo

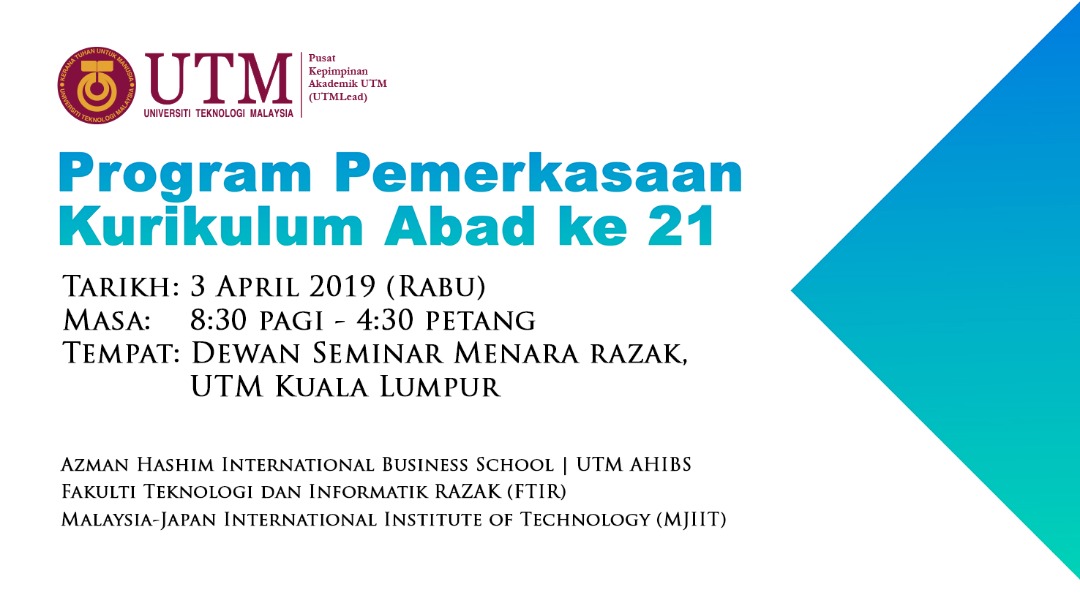

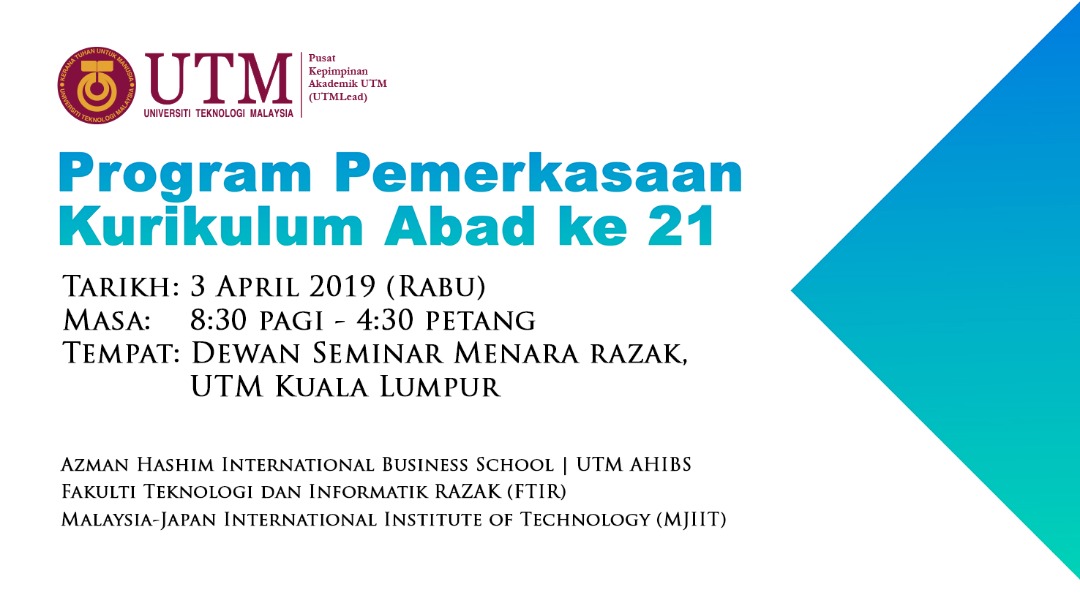

Program Pemerkasaan Kurikulum Abad ke 21 UTM KL : 3 April 2019

dan Salam Sejahtera

Y.Bhg.Datuk / Dato’ / Prof. / Prof. Madya / Dr. / Saudara,

Dipanjangkan.

Program yang dirancang adalah seperti berikut :

Tarikh : 3 April 2019 (Rabu)

Masa : 8.30 pagi – 4.30 petang

Tempat : Dewan Seminar, Menara Razak

Detail Program : Seperti di Lampiran

Merujuk kepada Timbalan Dekan (Akademik dan HEP), kehadiran diwajibkan kepada :

1. Pengarah

2. Penyelaras Program

3. TaskForce Program Baharu – Team Dr Fatimah bt Salim dan Team PM Dr Suriayati bt Chuprat.

Staf Akademik yang berkelapangan adalah sangat dialu-alukan untuk turut Hadir.

Atas keprihatinan, amat-amat dihargai.

innovative . entrepreneurial . global

Sekian, terima kasih.

by nurazaliah | Mar 18, 2019 | HowTo

Dear everyone,

You are cordially invited to the International Professional Doctorate Symposium (iPDOCs’19).

Date : 27th July 2019

Venue : Menara Razak, UTM Kuala Lumpur

The conference is jointly organized by the UTM School of Graduate Studies (SPS) and the Post Graduate Student Society (PGSS).

iPDOCs’ 19 is a profiling platform for the professional doctorate; a hybrid doctoral degree combining academic research with elements of practices that leverage on university-industry partnership.

This symposium aims to highlight the impacts of professional doctorate in developing professional practices, outcomes and achievements in industrial workplaces.

We invite presenters and participants including researchers, educators, students and practitioners to discuss their research activities, case studies, best practices and related contributions on the main theme of iPDOCs’19

Important Dates:

Abstract Submission: 10 April 2019

Notification of Acceptance: 30 April 2019

Full Paper Submission: 31 May 2019

Registration: 1 May – 1 July 2019

Details of the symposium can be obtained at http://www.utm.my/ipdocs. Should you have any inquiries, please email ipdocs@utm.my.

Thank you.

Best Regards,

iPDOCs’19 Secretariat

by nurazaliah | Mar 17, 2019 | HowTo

AMIDST a rapidly growing digital industry, the number of students taking Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) subject is dropping yearly.

It’s worrying that the talent pool continues to shrink despite STEM-related positions being among the top emerging jobs, said Education Minister Dr Maszlee Malik.

Last year only 44% of Malaysian students were in the STEM stream as compared to 48% in 2012, he said when delivering the keynote address at the Bett Asia Leadership Summit and Expo 2019 in Kuala Lumpur on Tuesday.

This represents an average reduction of around 6,000 students each year, a Bernama report quoted him as saying.

“Based on a 2017 report, 7% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is from digital products and services.

“The percentage is expected to increase to 45% four years from now,” Dr Maszlee said in the post, adding that four out of five new jobs in Malaysia is related to STEM fields.

Citing an example, he said the demand for data scientists in the country has risen by 15 fold between 2013 and 2017.

The declining interest in STEM was also seen in the 2018 Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia (STPM) results released on Monday.

A total of 42,849 science and social science candidates sat for the exam.

According to the Malaysian Examination Council STPM analysis report, 5,475 students took science subjects in the 2017 STPM, compared to 4,566 last year.

Of the 122 science stream students who achieved a cumulative grade point average (CGPA) of 4.0 last year, 51 were girls.

Although there were more candidates achieving grades C and above in Additional Mathematics, Physics, Biology, and Information and Communications Technology, last year, there was a 0.25% drop in Chemistry passes from the previous year. In 2018, the number of students enrolled in the science stream is only 167,962 out of 375,794. Also, more than 48% of Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM) candidates failed to get a grade C for Additional Mathematics, a prerequisite to enrol in STEM undergraduate courses, The Star reported last year.

And, 2017 statistics from the ministry showed that the number of students enrolled in fields related to Science, Mathematics, Computer, Engineering, Manufacturing, and Construction, at public and private higher learning institutions, was 334,742.

This was much lower than the 570,858 enrolled in Arts and Humanities, Education, Social Science, Business, and Law.

Read more at https://www.thestar.com.my/news/education/2019/03/17/interest-in-science-continues-to-drop/#HBHFWa1AGM0fI1KU.99

by nurazaliah | Mar 8, 2019 | HowTo

THE university rankers were up with their wares again last week, pronouncing this and that. Malaysians are informed of their “best” 10 with some holding their breath. Of the 10, I am closely associated with three at some point.

I should have been happy but not quite so because I am increasingly unsure of the worth of the ranking game. The issues I had for the last decade or so are still unresolved; they are getting more intense instead. I am of the opinion that the whole exercise is “intellectually dishonest”, perhaps bordering on unethical. It was then more of a hunch. Now it is more than just that.

Over time, evidence has been gathering pointing in that direction, at least in the Malaysian scene. For the discerning, a closer look at the existing league table will be sufficient to raise many questions — assuming one is not totally sold on the cliche that ranking “is here to stay”, a tagline often heavily promoted to subtly convey the message that not being ranked is a sure mark of “mediocrity”.

Like it or not, this is enough to scare many institutions resulting in total mental dependency on the league table mindset. And therefore, too, “afraid” to withdraw from the ranking game and the “negative” implications that are to follow, real or perceived. Including being condemned as “failing” even if the drop is a matter of one notch. In other words, one is stuck for life to a particular way of viewing a “university” according to set criteria preferred by a particular ranker (which itself can be just as mediocre).

It is, therefore, no wonder that no two rankers are alike because they are competing with one another. In fact, some rankers were known to be at loggerheads with each other in the rush to draw in as many clients as possible for better visibility, and for greater profitability. What is vital is the question of relevance to a particular worldview as to how one understands what education is truly about. More often it is slanted towards research and development, forcing many to readjust priorities, reluctantly, in the hope, they could be favourably ranked too. Other education missions like teaching and learning and community services are marginalised, although they are equally important if not more essential as the foundation to education.

It, therefore, implies if a university is not research biased, chances are it will be poorly ranked. Because research activities require deep pockets, the majority are not well positioned to meet the mark.

The Malaysian league table exemplifies this very well; the older and relatively mature institutions are better ranked. The reverse is also true. What is interesting is when a university that is not known for its research capacity also got ranked among the top 10. It may be a better teaching university instead, but that generally does not count. This can cause confusion leading to speculation as to what is meant by education if there are other sets of “hidden” rules or criteria that others are not privy to.

For example, what happens if there is a hypothetical case of a country wanting to focus more on “community engagement” as a core function of its education system? On top of that, it also wants to cherish values like love, happiness and mutual respect among members of the education sector. Or for that matter, not to link it to STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) but to STREAM (science, technology, religio-ethics, arts, management) backed by Sustainability Science or Education 2030. Do the universities of that country still have a choice to play the ranking game based on the old mantra as conventionally promoted by the rankers, and risk not being aligned with the country’s educational mission?

Put it another way, are the rankers more influential than the ministry of education in setting the priorities of the universities that are funded by the government? What is clear is that the present ranking game is no longer relevant to the new changing priorities as described.

This could be compounded when those changing priorities demand a different worldview of what quality education is all about (see CenPRIS, Feb 4). For example, in the context of Falsafah Pendidikan Kebangsaan. Here is where the notion of Education 2030 comes into the big picture in defining education in the context of the 21st century. In a manner of speaking, we need to be fully convinced that the ranking game is addressing such a concern as outlined by the global agenda of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (2016-2030). Otherwise, it is only logical to seriously consider skipping the ranking game that is at odds with our needs.

Recent Comments