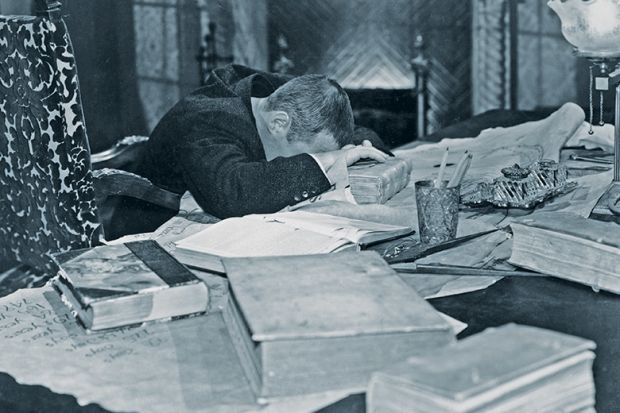

The majority of people working at universities find their job stressful, and academics are more prone to developing common mental health disorders than those working in other professions, according to a systematic review of published work on researchers’ well-being.

A lack of job security, limited support from management and the weight of work-related demands on their time were among the factors listed as affecting the health of those who work in higher education.

The report, commissioned by the Royal Society and the Wellcome Trust, urges institutions to work more closely with the UK’s regulator on health and safety in the workplace to address the risks to staff well-being.

For the study, research institute RAND Europe conducted a literature review to find out what is known about mental health in researchers, and identified 48 studies, which it analysed for the report entitled Understanding Mental Health in the Research Environment.

“Survey data indicate that the majority of university staff find their job stressful. Levels of burnout appear higher among university staff than in general working populations and are comparable to ‘high-risk’ groups such as healthcare workers,” write Susan Guthrie, a research leader at RAND, and colleagues in the report.

About 37 per cent of academics have common mental health disorders, which is a high level compared with other occupational groups. More than 40 per cent of postgraduate students report depression symptoms, emotional or stress-related problems or high levels of stress, they say.

“In large-scale surveys, UK higher education staff have reported worse well-being than staff in other types of employment in the areas of work demands, change management, support provided by managers and clarity about one’s role,” the report says.

Real and perceived job insecurity is an important issue for researchers, particularly those at the start of their careers who are often employed on a series of short-term contracts, the report adds.

Dr Guthrie and colleagues found that staff who devoted a lot of their working time to research experienced less stress than those who did not. But it was not clear whether this reduction in stress was related to the seniority of scientists who are able to spend time more on their research.

Among the report’s conclusions is a call for universities to work with the Health and Safety Executive to help address workplace stress. The organisation has issued management standards that describe how workplaces can identify and mitigate stress at an organisational level, they say.

“It could be useful to work through that approach with a university or a research organisation to identify the mechanisms at play in those environments. Doing so could establish the relevance of the approach in this context, and potentially provide a model that could be used more widely in the sector,” they add.

Recent Comments