A good read for undergraduate students.

LEAVE formal education in Malaysia these days and you find yourself swept into the path of a tornado —a vortex of skills disparity, mismatched expectations — that occurs even in a buoyant recruitment field.

The adage “Study hard, get a degree and your life will only get better” doesn’t quite ring true for thousands of graduates struggling to eke out a living, having spent at least four years in university buried in books. Right now, it’s almost impossible to shelter from the maelstrom.

In Malaysia, one in five young people is jobless. According to Bank Negara Malaysia (2017) in its Policy Outlook report, graduate unemployability in this country is a rising concern as graduates represent a whopping 23 per cent of total youth unemployment in the country.

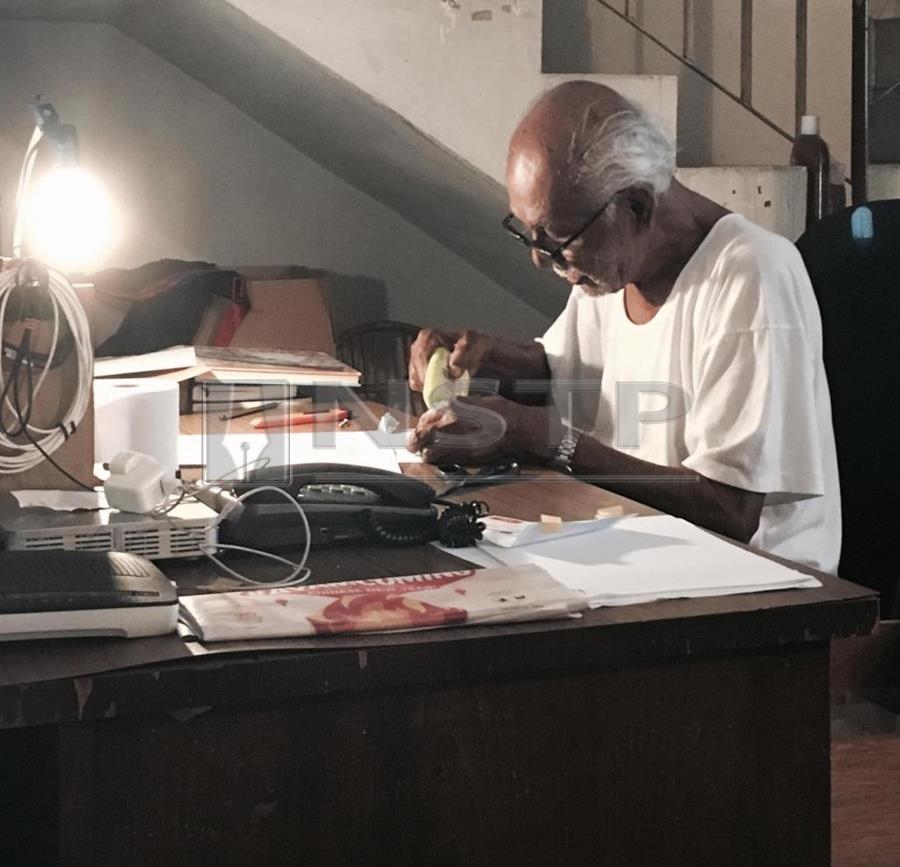

For Dr Seetha Nesaratnam, former lecturer and soft-skills trainer, the hard truth is obvious— being a university graduate no longer guarantees you a future that you envisioned for yourself. Getting a paper qualification doesn’t necessarily get you a job. And for Nesaratnam, she soon realised why.

In the bustling street of Little India, two young workers greeted Nesaratnam as she entered a jewellery shop. Striking a conversation with them, she asked whether they were students.

To her surprise, they answered: “No miss, we’re graduates.” She eventually discovered that they had trouble securing jobs befitting their education level.

“As I was speaking to them, I began to understand why these perfectly capable graduates who spent years and hard earned money studying for their degrees could not secure a job befitting their qualifications,” she recalls of her experience. It shocked her, she admits.

This incident, coupled with her growing concern that her own students, whom she was lecturing at a local university, would not be able to secure the jobs they were qualified for, resulted in a five year research study exploring graduate employability and their work-readiness from the perspective of employers and graduates.

Her study, Graduate Employability Model : A Malaysian Perspective, explores the issues pertaining to graduate unemployability in the country.

“When I started teaching in 2008, I had all types of students who walked through the corridors of the universities and into my classes,” she shares, adding: “I developed close relationships with them even after they graduated. I soon discovered that those who demonstrated leadership, exuded confidence, and took part in extracurricular activities including taking over projects and initiating discussions, were the ones who managed to secure good jobs. I had students who were bookworms, scoring high marks in their final exams… they simply couldn’t do the same.”

RESEARCH AND FINDINGS

The 49-year-old admits that her study wasn’t easy. “It was a challenge because of the methodology that I used. Most researchers would be satisfied with survey data, using statistical analysis tools to obtain results. I used that, and included qualitative data as well. I wanted to speak to the relevant people — employers, hirers and those handling young graduates. I wanted to find out the problems so I couldn’t simply rely on surveys alone.”

It took Nesaratnam five years to complete her study. And the results, she says, are eye-opening and true to what she realised when she spoke to the two workers at the jewellery shop a few years ago.

“I interviewed both graduates and employers, and soon realised that there was a growing mismatch of expectations from both parties when it came to securing a job.”

Her in-depth interviews with both employers and students led to her preliminary findings of a disparity between expectations, before she decided to embark on a research into this pertinent issue facing the country today.

Significant numbers of university leavers, she says, struggle to find graduate-level work, often because they do not understand what employers want. “You cannot simply rely on a degree alone to get a good job,” she reiterates.

Soft skills — sometimes known in work-speak as “employability skills” — are becoming increasingly important to graduate recruiters sifting through the CVs of a growing pool of similar-looking applicants, according to experts.

While hard skills refer to things such as academic qualifications, soft skills include communication ability, team-working, time management, problem-solving and attitude to work.

“There’s a dearth of soft skills in students. Most employers are searching for evidence of skills such as communication, teamwork, leadership, time management. These are referred to as ‘soft skills’ and they’ve never been more vital,” she says.

An international report cited that 62 per cent of business organisations in Malaysia mulled over the difficulty of hiring right skilled employees due to the shortage of general employability skills, particularly teamwork, communication in English, setting Malaysia as the highest in the Asean region.

Her research further showed that while employers prioritised communication, graduates viewed communication as the least essential element.

However, as for leadership qualities, graduates highlighted it as the most critical skill to have. Meanwhile, the employers took a contrasting viewpoint; that they can be trained to be leaders during their tenure of employment.

“In the case of the two young ladies I met in Little India, it was evident that they had difficulty in communicating in English. Ready or not, English is now the global language of business. More and more multinational companies are mandating English as the common corporate language in an attempt to facilitate communication and performance across geographically diverse functions and business endeavours,” she explains, adding emphatically: “If our graduates are let down by their own inability to communicate in this language, then what can we do to address this problem?”

TEACHING WITH A DIFFERENCE

For Nesaratnam, addressing the issues pertaining to soft-skills was something she undertook in addition to her role as a lecturer in a local university. “I’ve always emphasised soft-skills, long before I embarked on my study,” she confides, smiling.

It’s often said that outstanding lecturers or teachers demonstrate deep knowledge and understanding of their subjects. Although passion is inspiring, a deep knowledge and understanding of their students are just as important.

Her research is an extension of her on the-ground experiences garnered during her years as a lecturer at a local university, she tells me. “Those in the teaching profession must have a well-developed pastoral duty. As trusted adults, young people approach them with concerns and dilemmas, many of which relate to future aspirations. We have an obligation to work through these issues with young people in ways that help keep their sights on the bigger picture, and not just have a myopic view on their studies alone,” explains Nesaratnam.

While teaching, the disparity between scholarly achievements and soft skills wasn’t lost on her. “It goes back to back ground and upbringing. Middle class and upper middle class families do invest in their children’s soft-skill learnings like leadership and communication. These students fare better in the employment market later in life,” she says.

The others who don’t have these opportunities are disadvantaged, although they’re hardworking in class. “They did well in class but once they graduated, most, from my observations, didn’t do so well,” she laments. So Nesaratnam created a programme within the university called Professional Development and she taught it herself.

The programme covered elements such as self-confidence, communication skills and leadership — all of which, she attests, are non-negotiable attributes needed once a graduate enters the employment market. “I made it an elective course. I encouraged my students to take the course, and those who did received extra credits for their efforts,” she recalls.

The results were startling. Elaborates Nesaratnam: “I handpicked the students who needed the programme and I targeted those who struggled with confidence and poor communication skills. These are really good students who were hardworking but lacked the proper guidance in self development.”

As Nesaratnam’s former students, Hema Ganesan and Sarah Ashikin Mohamad Hedzir, would attest, the programme made a difference to them.

“I bloomed during my university days. Miss Seetha taught me to focus not just on my studies but also to build up other aspects of my personal development like communication, presentation and management skills. While my paper qualification was a step in the right direction, the other skills helped me secure employment right after my graduation,” shares Ganesan, who is currently a HR manager with a multinational company.

Assistant manager Sarah Ashikin agrees vehemently. “I still remember the presentation class that Miss Seetha taught — the gestures, how to make eye-contact and voice intonation. I followed those tips during my interview!” she recalls with a hearty laugh.

“Some of my friends and relatives obtained fantastic results but most of them have been unemployed for several months before finally getting a job. I realised that they didn’t acquire any soft-skill training at all. They just focused on their studies. I’m really grateful to have undergone some form of education in this aspect and I’ve had no issues securing a job right after my graduation.”

SOURCE OF INSPIRATION

The camaraderie between the former lecturer and her ex-students is evident. Nesaratnam tells me with a laugh that she’s in touch with most of her students and follows their progress with a lot of pride.

“Teaching has always been in my blood,” she reveals, attributing her passion in the profession to her late father, a World War II veteran who became a teacher after the war ended.

An English and Math teacher in the first English school in Malaya — the illustrious Clifford School in Kuala Kangsar — her father was keen on promoting extra-curricular activities and even produced Shakespearean plays.

“My father was a firm believer in an all rounded student. He emphasised that a person should be able to speak well, carry themselves well and write well. Unwittingly, he was one of those teachers who championed these additional attributes that are so important in the employment market today,” she says wistfully.

What advice would you give to university students today? I ask.

A pause and she eventually replies: “Take your university education seriously. It’s still the one that gets you that interview. But what will ultimately stand out are the other qualities. As important as it is to focus on the grades, it’s also important for a student to work on their other skills — that will make you stand out in an interview.”

She tells me of her student who was asked in an interview to give a presentation within 15 minutes. The student called her in panic, asking: “Miss, what do I do?” She told her student to use the same presentation she did during her Professional Development class. And she did. “She got the job!” says Nesaratnam, smiling.

For Nesaratnam, championing soft skills seems like an inherent trait she received from her father. “As an educator, I will never measure up to him,” she says softly, before sharing that when her father had an expensive surgery a few years ago, it was his former students (who were by then, in their seventies) who footed the entire bill.

“My father was already 94. Decades later, they still call him ‘Master’.” A pause and she concludes, her eyes glistening: “If I can achieve at least half of what he’s done for his students, I will be a very happy woman.”

Pengalaman belajar di universiti dulu sangat menarik. Saya antara pelajar yang dapat keputusan akademik yang baik zaman universiti dulu. Pernah ada semester yang saya dapat pointer 4.00 dan menjadi pelajar pertama UiTM Kampus Machang yang pernah dapat pointer itu. Maksudnya, semua subjek saya dapat skor A atau A+ untuk satu semester tu.

Pengalaman belajar di universiti dulu sangat menarik. Saya antara pelajar yang dapat keputusan akademik yang baik zaman universiti dulu. Pernah ada semester yang saya dapat pointer 4.00 dan menjadi pelajar pertama UiTM Kampus Machang yang pernah dapat pointer itu. Maksudnya, semua subjek saya dapat skor A atau A+ untuk satu semester tu. “Kalau pergi universiti dan belajar, mesti dapat 3 pointer mak cik. Kalau rajin sikit lagi, mesti pointer dia 3.50 ke atas! Yang tak lulus tu sebenarnya dia bermain di universiti. Bukan pergi belajar…” kata saya pada makcik yang anaknya akan ke universiti.

“Kalau pergi universiti dan belajar, mesti dapat 3 pointer mak cik. Kalau rajin sikit lagi, mesti pointer dia 3.50 ke atas! Yang tak lulus tu sebenarnya dia bermain di universiti. Bukan pergi belajar…” kata saya pada makcik yang anaknya akan ke universiti.