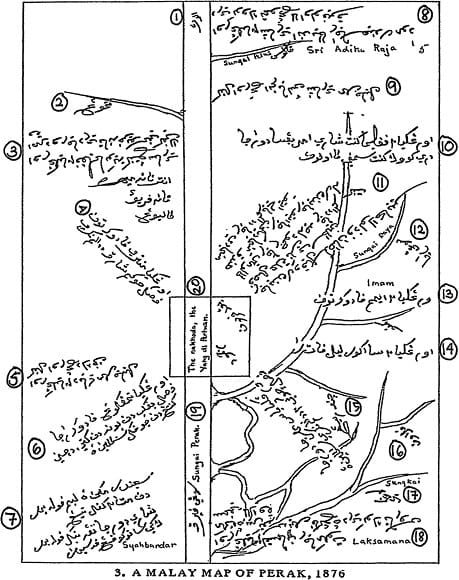

In 1876, a Malay map of Perak, based on W.E. Maxwell’s notes and sourced from MS 46943 at the Royal Asiatic Society in London, was published in Barbara Andaya’s work, “Perak: The Abode of Grace: A Study of an Eighteenth Century Malay State” (1979). In this map, some words, including place names and court noble titles, have been transliterated by Andaya. The Arabic numerals enclosed in circles serve as the author’s annotations, aiding in the transliteration and translation of Jawi text into Romanized Malay and English.

This map may strike readers as unusual, as it lacks common features found in contemporary geographical maps, such as border lines, legends, a metrical scale, and a compass. In the Malay text “Misa Melayu,” the term “peta” (map) doesn’t appear in its base form but rather as a passive verb twice: once to describe the vivid imagery of a noble (Orangkaya Temenggung) conjured in one’s thoughts and another time to depict the creation of a blueprint for a ship.

It becomes apparent that the 1876 map wasn’t primarily a navigational tool for the Malays of eighteenth-century Perak. Instead, it served as a representation of human imagination, depicting the riverine state on paper.

As part of the collection of historical documents concerning Perak’s statecraft in the eighteenth century, the 1876 map holds immense historical value. It tells an alternative story of how the state may have been envisioned in the past, intertwining the flow of the Perak River and its tributaries with the titles of court royals.

When examining this map alongside “Misa Melayu,” a text that not only celebrates the present but also the signs of that era—such as a new city, a fort, or a mosque—it’s possible to see the map itself as a representation of the present or modernity. However, it remains as enigmatic as the text. It’s plausible that this map, much like “Misa Melayu,” was created at the request of a modernized sultan who aimed to present the state in a way understandable to Europeans and other foreign elites or merchants engaging with the state government at that time.

One can easily imagine the map being kept by Perak’s elites, possibly within the sultan’s regalia, similar to depictions of European monarchs with globes or maps in the background in old paintings. Like many maps from the 1800s and earlier, the 1876 map was likely a repository of knowledge considered secret, sacred, and accessible only to a select few—the royal elites and British officers.

In the past, Jawi script was widely used, even by British colonial authorities. It raises the question of why, in contemporary times, many Malaysians seem to be moving away from its use and not actively preserving it. This comment highlights an intriguing aspect of cultural and linguistic shifts that merit further exploration in the context of Jawi script and its cultural significance in Malaysia.

Sources: FB: The Interesting Historical Facts of Malaysia